Chapter 04 - Language and Knowledge of the World

Dr. Montessori's Own Handbook - Restoration

# [Chapter 04 - Language and Knowledge of the World](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+04+-+Language+and+Knowledge+of+the+World#chapter-04---language-and-knowledge-of-the-world)

The special importance of the sense of hearing comes from the fact that it is the sense organ connected with speech. Therefore, to train the child’s attention to follow sounds and noises which are produced in the environment, recognize them, and discriminate between them, is to prepare his attention to follow more accurately the sounds of articulate language. The teacher must be careful to pronounce clearly and completely the sounds of the word when she speaks to a child, even though she may be speaking in a low voice, almost as if telling him a secret. The children’s songs are also a good means for obtaining exact pronunciation. The teacher, when she teaches them, pronounces slowly, separating the component sounds of the word pronounced.

But a special opportunity for training in clear and exact speech occurs when the lessons are given in the nomenclature relating to the sensory exercises. In every exercise, when the child has ***recognized*** the differences between the qualities of the objects, the teacher fixes the idea of this quality with a word. Thus, when the child has many times built and rebuilt the tower of the pink cubes, at an opportune moment the teacher draws near him, and taking the two extreme cubes, the largest and the smallest, and showing them to him, says,

* T: “This is large”;

* T: “This is small.”

* The two words only, ***large*** and ***small***, are pronounced several times in succession with a strong emphasis and with very clear pronunciation,

* T: “This is ***large***, large, large”;

* after which there is a moment’s pause.

* Then the teacher, to see if the child has understood, verifies with the following tests:

* T: “Give me the large one. Give me the ***small*** one.”

* T: Again, “The large one.”

* T: “Now the small one.”

* T: “Give me the large one.”

* Then there is another pause.

* Finally, the teacher, pointing to the objects in turn asks,

* T: “What is this?”

* The child, if he has learned, replies rightly,

* C: “Large,” “Small.”

* The teacher then urges the child to repeat the words always more clearly and as accurately as possible.

* T: “What is it?”

* C: “Large.”

* T: “What?”

* C: “Large.”

* T: “Tell me nicely, what is it?”

* C: “Large.”

***Large*** and ***small*** objects are those which differ only in size and not in form; that is, all three dimensions change more or less proportionally. We should say that a house is “large” and a hut is “small.” When two pictures represent the same objects in different dimensions one can be said to be an enlargement of the other.

When, however, only the dimensions referring to the section of the object change, while the length remains the same, the objects are respectively “thick” and “thin.” We should say of two posts of equal height, but different cross-sections, that one is “thick” and the other is “thin.” The teacher, therefore, gives a lesson on the brown prisms similar to that with the cubes in the three “periods” which I have described:

* ***Period 1. Naming.*** “This is thick. This is thin.”

* ***Period 2. Recognition.*** “Give me the *thick*. Give me the *thin*.”

* ***Period 3. The Pronunciation of the Word.*** “What is this?”

There is a way of helping the child to recognize differences in dimension and to place the objects in the correct gradation. After the lesson which I have described, the teacher scatters the brown prisms, for instance, on a carpet, says to the child, “Give me the thickest of all,” and lays the object on a table. Then, again, she invites the child to look for ***the thickest*** piece among those scattered on the floor, and every time the piece chosen is laid in its order on the table next to the piece previously chosen. In this way, the child accustoms himself always to look either for the ***thickest*** or the ***thinnest*** among the rest and so has a guide to help him to lay the pieces in gradation.

When there is one dimension only which varies, as in the case of the rods, the objects are said to be “long” and “short,” the varying dimension being length. When the varying dimension is height, the objects are said to be “tall” and “short”; when the breadth varies, they are “broad” and “narrow.”

Of these three varieties, we offer the child as a fundamental lesson only that in which the ***length*** varies, and we teach the differences utilizing the usual “three periods,” and by asking him to select from the pile at one time always the “longest,” at another always the “shortest.”

The child in this way acquires great accuracy in the use of words. One day the teacher ruled the blackboard with very fine lines. A child said, “What small lines!” “They are not small,” corrected another; “they are ***thin***.”

When the names to be taught are those of colors or of forms, so that it is not necessary to emphasize the contrast between extremes, the teacher can give more than two names at the same time, as, for instance,

* T: “This is red.”

* T: “This is blue.”

* T: “This is yellow.”

Or, again,

* T: “This is a square.”

* T: “This is a triangle.”

* T: “This is a circle.”

In the case of a ***gradation***, however, the teacher will select (if she is teaching the colors) the two extremes “dark” and “light,” then making choice always of the “darkest” and the “lightest.”

Many of the lessons here described can be seen in the cinematograph pictures; lessons on touching the plane insets and the surfaces, walking on the line, color memory, the nomenclature relating to the cubes, and the long rods, the composition of words, reading, writing, etc.

Using these lessons the child comes to know many words very thoroughly - large, small; thick, thin; long, short; dark, light; rough, smooth; heavy, light; hot, cold; and the names of many colors and geometrical forms. Such words do not relate to any particular *object*, but to a psychic acquisition on the part of the child. In fact, the name is given ***after a long exercise***, in which the child, concentrating his attention on different qualities of objects, has made comparisons, reasoned, and formed judgments until he has acquired a power of discrimination that he did not possess before. In a word, he has ***refined his senses***; his observation of things has been thorough and fundamental; he has ***changed himself***.

He finds himself, therefore, facing the world with *psychic* qualities refined and quickened. His powers of observation and of recognition have greatly increased. Further, the mental images which he has succeeded in establishing are not a confused medley; they are all classified - forms are distinct from dimensions, and dimensions are classed according to the qualities which result from the combinations of varying dimensions.

All these are quite distinct from ***gradations***. Colors are divided according to tint and richness of tone, silence is distinct from non-silence, noises from sounds, and everything has its own exact and appropriate name. The child then has not only developed in himself special qualities of observation and of judgment, but the objects which he observes may be said to go into their place, according to the order established in his mind, and they are placed under their appropriate name in an exact classification.

Does not the student of the experimental sciences prepare himself in the same way to observe the outside world? He may find himself like the uneducated man amid the most diverse natural objects, but he differs from the uneducated man in that he has ***special qualities*** for observation. If he is a worker with a microscope, his eyes are trained to see in the range of the microscope certain minute details that the ordinary man cannot distinguish. If he is an astronomer, he will look through the same telescope as the curious visitor or ***dilettante***, but he will see much more clearly. The same plants surround the botanist and the ordinary wayfarer, but the botanist sees in every plant those qualities which are classified in his mind, and assigns each plant its own place in the natural orders, giving it its exact name. It is this capacity for recognizing a plant in a complex order of classification which distinguishes the botanist from the ordinary gardener, and it is ***an exact*** and scientific language that characterizes the trained observer.

Now, the scientist who has developed special qualities of observation and who “possesses” an order in which to classify external objects will be the man to make scientific ***discoveries***. It will never be he who, without preparation and order, wanders dreaming among plants or beneath the starlit sky.

In fact, our little ones have the impression of continually “making discoveries” in the world about them; and in this, they find the greatest joy. They take from the world knowledge which is ordered and inspire them with enthusiasm. Into their minds there enters “the Creation” instead of “the Chaos”; and it seems that their souls find therein divine exultation.

---

## [Freedom](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+04+-+Language+and+Knowledge+of+the+World#freedom)

The success of these results is closely connected with the delicate intervention of the one who guides the children in their development. The teacher must guide the child without letting him feel her presence too much, so that she may be always ready to supply the desired help, but may never be the obstacle between the child and his experience.

A lesson in the ordinary use of the word cools the child’s enthusiasm for the knowledge of things, just as it would cool the enthusiasm of adults. To keep alive that enthusiasm is the secret of real guidance, and it will not prove a difficult task, provided that the attitude towards the child’s acts be that of respect, calm, and waiting, and provided that he is left free in his movements and in his experiences.

Then we shall notice that the child has a personality which he is seeking to expand; he has initiative, he chooses his own work, persists in it, and changes it according to his inner needs; he does not shirk effort, he rather goes in search of it, and with great joy overcomes obstacles within his capacity. He is sociable to the extent of wanting to share with everyone his successes, his discoveries, and his little triumphs. There is therefore no need for intervention. “Wait while observing.” That is the motto of the educator.

Let us wait, and be always ready to share in both the joys and the difficulties which the child experiences. He invites our sympathy, and we should respond fully and gladly. Let us have endless patience with his slow progress, and show enthusiasm and gladness at his successes. If we could say: “We are respectful and courteous in our dealings with children, we treat them as we should like to be treated ourselves,” we should certainly have mastered a great educational principle and undoubtedly be setting an ***example of a good education***.

What we all desire for ourselves, namely, not to be disturbed in our work, not to find hindrances to our efforts, to have good friends ready to help us in times of need, to see them rejoice with us, to be on terms of equality with them, to be able to confide and trust in them––this is what we need for happy companionship. In the same way, children are human beings to whom respect is due, superior to us because of their “innocence” and of the greater possibilities of their future. What we desire they desire also.

As a rule, however, we do not respect our children. We try to force them to follow us without regard to their special needs. We are overbearing with them, and above all, rude; and then we expect them to be submissive and well-behaved, knowing all the time how strong their instinct of imitation and how touching their faith in and admiration of us. They will imitate us in any case. Let us treat them, therefore, with all the kindness which we would wish to help to develop in them. And by kindness is not meant caresses. Should we not call anyone who embraced us at the first time meeting rude, vulgar and ill-bred? Kindness consists in interpreting the wishes of others, conforming one’s self to them, and sacrificing, if need be, one’s own desire. This is the kindness which we must show towards children.

To find the interpretation of children’s desires we must study them scientifically, for their desires are often unconscious. They are the inner cry of life, which wishes to unfold according to mysterious laws. We know very little of how it unfolds. Certainly, the child is growing into a man by force of a divine action similar to that by which from nothing he became a child.

Our intervention in this marvelous process is ***indirect***; we are here to offer to this life, which came into the world by itself, the ***means*** necessary for its development, and having done that we must await this development with respect.

Let us leave life ***free*** to develop within the limits of the good, and let us observe this inner life developing. This is the whole of our mission. Perhaps as we watch we shall be reminded of the words of Him who was absolutely good, “Suffer the little children to come unto Me.” That is to say, “Do not hinder them from coming, since, if they are left free and unhampered, they will come.”

---

## [Writing](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+04+-+Language+and+Knowledge+of+the+World#writing)

The child who has completed all the exercises above described, and is thus ***prepared*** for an advance toward unexpected conquests, is about four years old.

He is not an unknown quantity, as are children who have been left to gain varied and casual experiences by themselves, and who therefore differ in type and intellectual standard, not only according to their “natures,” but especially according to the chances and opportunities they have found for their spontaneous inner formation.

Education has ***determined an environment*** for the children. Individual differences to be found in them can, therefore, be put down almost exclusively to each one’s individual “nature.” Owing to their environment which offers ***means*** adapted and measured to meet the needs of their psychical development, our children have acquired a fundamental type that is common to all. They have ***coordinated*** their movements in various kinds of manual work about the house, and so have acquired characteristic independence of action, and initiative in the adaptation of their actions to their environment. Out of all this emerges a ***personality***, for the children have become little men, who are self-reliant.

The special attention necessary to handle small fragile objects without breaking them, and to move heavy articles without making a noise, has endowed the movements of the whole body with a lightness and grace which are characteristic of our children. It is a deep feeling of responsibility that has brought them to such a pitch of perfection. For instance, when they carry three or four tumblers at a time or a tureen of hot soup, they know that they are responsible not only for the objects but also for the success of the meal which at that moment they are directing. In the same way, each child feels the responsibility of the “silence,” of the prevention of harsh sounds, and he knows how to cooperate for the general good in keeping the environment, not only orderly but quiet and calm. Indeed, our children have taken the road which leads them to mastery of themselves.

But their formation is due to a deeper psychological work still, arising from the education of the senses. In addition to ordering their environment and ordering themselves in their outward personalities, they have also ordered the inner world of their minds.

The didactic material, in fact, does not offer to the child the “content” of the mind, but the ***order*** for that “content.” It causes him to distinguish identities from differences, extreme differences from fine gradations, and to classify, under conceptions of quality and of quantity, the most varying sensations appertaining to surfaces, colors, dimensions, forms, and sounds. The mind has formed itself by a special exercise of attention, observing, comparing, and classifying.

The mental attitude acquired by such an exercise leads the child to make ordered observations in his environment, observations which prove as interesting to him as discoveries, and so stimulate him to multiply them indefinitely and to form in his mind a rich “content” of clear ideas.

The language now comes to ***fix*** using ***exact words*** the ideas which the mind has acquired. These words are few in number and have a reference, not to separate objects, but rather to the ***order of the ideas*** which have been formed in the mind. In this way, the children can “find themselves,” alike in the world of natural things and in the world of objects and of words that surround them, for they have an inner guide that leads them to become ***active and intelligent explorers*** instead of wandering wayfarers in an unknown land.

These are the children who, in a short space of time, sometimes in a few days, learn to write and perform the first operations of arithmetic. It is not a fact that children, in general, can do it, as many have believed. It is not a case of giving my material for writing to unprepared children and of awaiting the “miracle.”

The fact is that the minds and hands of our children are already ***prepared*** for writing, and ideas of quantity, identity, differences, and gradation, which form the bases of all calculations, have been maturing for a long time in them.

One might say that all their previous education is a preparation for the first stages of essential culture - ***writing***\*\*, *reading*, *and number*\*\* and that knowledge comes as an easy, spontaneous, and logical consequence of the preparation - it is in fact natural ***conclusion***.

We have already seen that the purpose of the ***word*** is to fix ideas and to facilitate the elementary comprehension of ***things***. In the same way writing and arithmetic now fix the complex inner acquisitions of the mind, which proceeds henceforward continually to enrich itself by fresh observations.

Our children have long been preparing their hands for writing. Throughout all the sensory exercises the hand, whilst cooperating with the mind in its attainments and in its work of formation, was preparing its own future. When the hand learned to hold itself lightly suspended over a horizontal surface to touch rough and smooth when it took the cylinders of the solid insets and placed them in their apertures when with two fingers it touched the outlines of the geometrical forms, it was coordinating movements, and the child is now ready - almost impatient to use them in the fascinating “synthesis” of writing.

The ***direct*** preparation for writing also consists of exercises in the movements of the hand. There are two series of exercises, very different from one another. I have analyzed the movements which are connected with writing, and I prepare them separately one from the other. When we write, we perform a movement for the ***management*** of the instrument of writing, a movement which generally acquires an individual character, so that a person’s handwriting can be recognized, and, in certain medical cases, changes in the nervous system can be traced by the corresponding alterations in the handwriting. In fact, it is from the handwriting that specialists in that subject would interpret the ***moral character*** of individuals.

Writing has, besides this, a general character, which has reference to the form of the alphabetical signs.

When a man writes he combines these two parts, but they actually exist as the ***component parts of a single product*** and can be prepared apart.

## ***[Exercises for the Management of the Instrument of Writing](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+04+-+Language+and+Knowledge+of+the+World#exercises-for-the-management-of-the-instrument-of-writing)***

(The Individual Part)

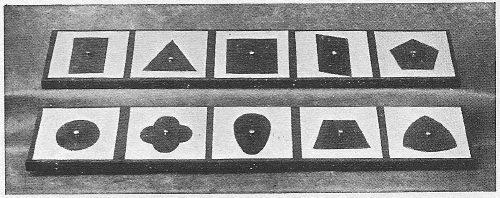

In the didactic material, there are two sloping wooden boards, on each of which stand five square metal frames, colored pink. In each of these is inserted a blue geometrical figure similar to the geometrical insets and provided with a small button for a handle. With this material, we use a box of ten colored pencils and a little book of designs which I have prepared after five years’ experience of observing the children. I have chosen and graduated the designs according to the use which the children made of them.

The two sloping boards are set side by side, and on them are placed ten complete “insets,” that is to say, the frames with the geometrical figures. (Fig. 28.) The child is given a sheet of white paper and a box of ten colored pencils. He will then choose one of the ten metal insets, which are arranged in an attractive line at a certain distance from him. The child is taught the following process:

> Fig. 28. - Sloping Boards to Display Set of Metal Insets.

He lays the frame of the iron inset on the sheet of paper, and, holding it down firmly with one hand, he follows with a colored pencil the interior outline which describes a geometrical figure. Then he lifts the square frame and finds drawn upon the paper an enclosed geometrical form, a triangle, a circle, a hexagon, etc. The child has not actually performed a new exercise, because he had already performed all these movements when he ***touched*** the wooden plane insets. The only new feature of the exercise is that he follows the outlines no longer directly with his finger but through the medium of a pencil. That is, he ***draws, he leaves a trace*** of his movement.

The child finds this exercise easy and most interesting, and, as soon as he has succeeded in making the first outline, he places above it the piece of blue metal corresponding to it. This is an exercise exactly similar to that which he performed when he placed the wooden geometrical figures upon the cards of the third series, where the figures are only contained by a simple line.

This time, however, when the action of placing the form upon the outline is performed, the child takes ***another colored pencil*** and draws the outline of the blue metal figure.

When he raises it, if the drawing is well done, he finds upon the paper a geometrical figure contained by two outlines in colors, and, if the colors have been well chosen, the result is very attractive, and the child, who has already had a considerable education of the chromatic sense is keenly interested in it.

These may seem unnecessary details, but, as a matter of fact, they are all-important. For instance, if, instead of arranging the ten metal insets in a row, the teacher distributes them among the children without thus exhibiting them, the child’s exercises are much limited. When, on the other hand, the insets are exhibited before his eyes, he feels the desire to draw them ***all*** one after the other, and the number of exercises is increased.

The two ***colored outlines*** rouse the desire of the child to see another combination of colors and then to repeat the experience. The variety of the objects and the colors are therefore an ***inducement*** to work and hence to final success.

Here the actual preparatory movement for writing begins. When the child has drawn the figure in double outline, he takes hold of a pencil “like a pen for writing,” and draws marks up and down until he has completely filled the figure. In this way, a definite filled-in figure remains on the paper, similar to the figures on the cards of the first series. This figure can be in any of the ten colors. At first, the children fill in the figures very clumsily without regard for the outlines, making very heavy lines and not keeping them parallel. Little by little, however, the drawings improve, in that they keep within the outlines, and the lines increase in number, grow finer, and are parallel to one another.

When the child has begun these exercises, he is seized with a desire to continue them, and he never tires of drawing the outlines of the figures and then filling them in. Each child suddenly becomes the possessor of a considerable number of drawings, and he treasures them up in his own little drawer. In this way, he ***organizes*** the movement of writing, which brings him ***to the management of the pen***. This movement in ordinary methods is represented by the wearisome pothook connected with the first laborious and tedious attempts at writing.

The organization of this movement, which began from the guidance of a piece of metal, is as yet rough and imperfect, and the child now passes on to the ***filling in of the prepared designs*** in the little album. The leaves are taken from the book one by one in the order of progression in which they are arranged, and the child fills in the prepared designs with colored pencils in the same way as before. Here the choice of colors is another intelligent occupation that encourages the child to multiply the tasks. He chooses the colors by himself and with much taste. The delicacy of the shades which he chooses and the harmony with which he arranges them in these designs show us that the common belief, that children love ***bright and glaring*** colors, has been the result of observation of ***children without education***, who have been abandoned to the rough and harsh experiences of an environment unfitted for them.

The education of the chromatic sense becomes at this point of a child’s development the ***lever*** which enables him to become possessed of a firm, bold and beautiful handwriting.

The drawings lend themselves to ***limiting***, in very many ways, ***the length of the strokes with which they are filled in***. The child will have to fill in geometrical figures, both large and small, of a pavement design, flowers, and leaves, or the various details of an animal or a landscape. In this way the hand accustoms itself, not only to perform the general action but also to confine the movement within all kinds of limits.

Hence the child is preparing himself to write in handwriting ***either*** large or small. Indeed, later on, he will write as well between the wide lines on a blackboard as between the narrow, closely ruled lines of an exercise book, generally used by much older children.

The number of exercises that the child performs with the drawings is practically unlimited. He will often take another colored pencil and draw over again the outlines of the figure already filled in with color. Help to the ***continuation*** of the exercise is to be found in the further education of the chromatic sense, which the child acquires by painting the same designs in watercolors. Later he mixes colors for himself until he can imitate the colors of nature, or create the delicate tints which his own imagination desires. It is not possible, however, to speak of all this in detail within the limits of this small work.

## ***[Exercises for the Writing of Alphabetical Signs](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+04+-+Language+and+Knowledge+of+the+World#exercises-for-the-writing-of-alphabetical-signs)***

> Fig. 29. - Single Sandpaper Letter.

> Fig. 30. - Groups of Sandpaper Letters.

In the didactic material, there are a series of boxes that contain alphabetical signs. At this point we take those cards which are covered with very smooth paper, to which is gummed a letter of the alphabet cut out in sandpaper. (Fig. 29.) There are also large cards on which are gummed several letters, grouped together according to the analogy of form. (Fig. 30.)

The children “have to ***touch*** over the alphabetical signs as though they were writing.” They touch them with the tips of the index and middle fingers in the same way as when they touched the wooden insets, and with the hand raised as when they lightly touched the rough and smooth surfaces. The teacher herself touches the letters to show the child how the movement should be performed, and the child, if he has had much practice in touching the wooden insets, ***imitates*** her with *ease* and pleasure. Without the previous practice, however, the child’s hand does not follow the letter with accuracy, and it is most interesting to make close observations of the children to understand the importance of ***remote motor preparation*** for writing, and also to realize the ***immense*** strain which we impose upon the children when we set them to write directly without a previous motor education of the hand.

The child finds great pleasure in touching the sandpaper letters. It is an exercise by which he applies to new attainment the power he has already acquired through exercising the sense of touch. Whilst the child touches a letter, the teacher pronounces its sound, and she uses for the lesson the usual three periods. Thus, for example, presenting the two vowels ***i***, *o*, she will have the child touch them slowly and accurately, and repeat their relative sounds one after the other as the child touches them, “i, i, i! o, o, o!” Then she will say to the child: “Give me i!” “Give me o!” Finally, she will ask the question: “What is this?” To which the child replies, “i, o.” She proceeds in the same way through all the other letters, giving, in the case of the consonants, not the name, but only the sound. The child then touches the letters by himself over and over again, either on the separate cards or on the large cards on which several letters are gummed and in this way he establishes the movements necessary for tracing the alphabetical signs. At the same time, he retains the ***visual*** image of the letter. This process forms the first preparation, not only for writing, but also for reading, because it is evident that when the child ***touches*** the letters he performs the movement corresponding to their writing them, and, at the same time, when he recognizes them by sight he is reading the alphabet.

The child has thus prepared, in effect, all the necessary movements for writing; therefore he ***can write***. This important conquest is the result of a long period of inner formation of which the child is not clearly aware. But a day will come - very soon - when he ***will write***, and that will be a day of great surprise for him - the wonderful harvest of unknown sowing.

---

> Fig. 31. - Box of Movable Letters.

The alphabet of movable letters cut out in pink and blue cardboard and kept in a special box with compartments, serves “for the composition of words.” (Fig. 31.)

In a phonetic language, like Italian, it is enough to pronounce clearly the different component sounds of a word (as, for example, m-a-n-o), so that the child whose ear is ***already educated*** may recognize one of one the component sounds. Then he looks in the movable alphabet for the ***signs*** corresponding to each separate sound and lays them one beside the other, thus composing the word (for instance, mano). Gradually he will become able to do the same thing with words of which he thinks himself; he succeeds in breaking them up into their component sounds, and in translating them into a row of signs.

When the child has composed the words in this way, he knows how to read them. In this method, therefore, all the processes leading to writing include reading as well.

If the language is not phonetic, the teacher can compose separate words with the movable alphabet, and then pronounce them, letting the child repeat by himself the exercise of arranging and rereading them.

In the material, there are two movable alphabets. One of them consists of larger letters and is divided into two boxes, each of which contains the vowels. This is used for the first exercise, in which the child needs very large objects to recognize the letters. When he is acquainted with one-half of the consonants he can begin to compose words, even though he is dealing with one part only of the alphabet.

The other movable alphabet has smaller letters and is contained in a single box. It is given to children who have made their first attempts at composition with words and already know the complete alphabet.

It is after these exercises with the movable alphabet that the child ***can write entire words***. This phenomenon generally occurs unexpectedly, and then a child who has never yet traced a stroke or a letter on paper ***writes several words in succession***. From that moment he continues to write, always gradually perfecting himself. This spontaneous writing takes on the characteristics of a ***natural*** phenomenon, and the child who has begun to write the “first word” will continue to write in the same way as he spoke after pronouncing the first word, and as he walked after having taken the first step. The same course of inner formation through which the phenomenon of writing appeared in the course of his future progress, of his growth to perfection. The child prepared in this way has entered upon a course of development through which he will pass as surely as the growth of the body and the development of the natural functions have passed through their course of development when life has once been established.

For the interesting and very complex phenomena relating to the development of writing and then reading, see my larger works.

> ##### **The license of this page:**

>

> This page is part of the “**Montessori Restoration and Translation Project**”.

>

> Please [support](https://ko-fi.com/montessori) our “**All-Inclusive Montessori Education for All 0-100+ Worldwide**” initiative. We create open, free, and affordable resources available for everybody interested in Montessori Education. We transform people and environments to be authentic Montessori worldwide. Thank You!

>

> [](http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/)

>

> **License:** This work with all its restoration edits and translations is licensed under a [Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License](http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/).

>

> Check out the **Page History** of each wiki page in the right column to learn more about all contributors and edits, restorations, and translations done on this page.

>

> [Contributions](https://mariamontessori.xyz/s/montessorix/wiki/page/view?title=Contribute+to+Montessori+X) and [Sponsors](https://mariamontessori.xyz/s/montessorix/wiki/page/view?title=Support+Montessori+X) are welcome and very appreciated!

>

> ### The book itself is protected under **The Project Gutenberg License**

>

> [https://www.gutenberg.org/policy/license.html](https://www.gutenberg.org/policy/license.html)

>

> To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work (or any other work associated in any way with the phrase “Project Gutenberg”), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at [www.gutenberg.org/license](https://www.gutenberg.org/license)

>

> **This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away, or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at [www.gutenberg.org](http://www.gutenberg.org/). If you are not located in the United States, you’ll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.**

>

> Read this book on …

>

> **[Project Gutenberg](https://www.gutenberg.org/)**

>

> * [https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/29635](https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/29635)

>

> **[Archive.org](http://archive.org/)**

>

> * [https://archive.org/details/drmontessorisow01montgoog/](https://archive.org/details/drmontessorisow01montgoog/)

> * [https://archive.org/details/drmontessorisown01mont/](https://archive.org/details/drmontessorisown01mont/)

> * [https://archive.org/details/drmontessorisown00mont](https://archive.org/details/drmontessorisown00mont)

> * [https://archive.org/details/drmontessorisown29635gut](https://archive.org/details/drmontessorisown29635gut)

>

> **[Guides.co](https://guides.co/)**

>

> * [https://guides.co/g/montessori-handbook/31826](https://guides.co/g/montessori-handbook/31826)

* [Dr. Montessori's Own Handbook](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/English "Dr. Montessori's Own Handbook") - English Restoration - [Archive.Org](https://archive.org/details/drmontessorisown01mont/page/n5/mode/2up "Dr. Montessori's Own Handbook on Archive.Org") - [Project Gutenberg](https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/29635 "Dr. Montessori's Own Handbook on Project Gutenberg")

* [0 - Chapter Index - Dr. Montessori's Own Handbook - Restoration](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/0+-+Chapter+Index+-+Dr.+Montessori%27s+Own+Handbook+-+Restoration)

* [Chapter 00 – Dedication, Acknowledgements, Preface](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+00+%E2%80%93+Dedication%2C+Acknowledgements%2C+Preface)

* [Chapter 01 - Introduction - Children's House - The Method](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+01+-+Introduction+-+Children%27s+House+-+The+Method)

* [Chapter 02 - Motor Education](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+02+-+Motor+Education)

* [Chapter 03 - Sensory Education](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+03+-+Sensory+Education)

* [Chapter 04 - Language and Knowledge of the World](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+04+-+Language+and+Knowledge+of+the+World)

* [Chapter 05 - The Reading of Music](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+05+-+The+Reading+of+Music)

* [Chapter 06 - Arithmetic](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+06+-+Arithmetic)

* [Chapter 07 - Moral Factors](https://montessori-international.com/s/montessoris-own-handbook/wiki/Chapter+07+-+Moral+Factors)